The fluctuation of hormones throughout the menstrual cycle is a normal process that supports ovulation and menstruation. Unfortunately, for some women, the inherent fluctuation of their hormones creates a rollercoaster of physical and emotional symptoms that can be extreme to the point of intolerable. While all women experience hormonal fluctuations throughout their cycle, some women experience only mild discomfort while other women feel as if their world is crashing around them.

Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) are premenstrual disorders characterized by physical and psychological symptoms that occur in the luteal phase (after ovulation) of the menstrual cycle. PMS affects 20-40% of menstruating women and common symptoms include fatigue, irritability, mood swings, depression, abdominal bloating, breast tenderness, acne, changes in appetite and food cravings. PMDD occurs in 5-8% of menstruating women and is characterized by extreme mood and physical symptoms to such a degree that it is difficult to function in daily life (1).

Currently, PMDD is listed as a depressive disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) but it was not until 1987 that formal criteria for this diagnosis were proposed. While the pathophysiology of PMDD remains unclear, it has been hypothesized that sensitivity to hormonal fluctuations during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, abnormal serotonergic activity, genetic variations, and aberrations in progesterone, estrogen and GABA may all play a role (1).

In the first part of this two-part series, we will explore the symptoms, risk factors, diagnosis, and the relationship of progesterone and its main metabolite, allopregnanolone (ALLO), to the function of GABA-A receptors. GABA is our main inhibitory neurotransmitter and is associated with reducing anxiety and inducing a sense of calm. Reduced sensitivity between GABA-A receptors and the presence of ALLO is considered the main pathogenic factor in the development of PMDD (2).

Common symptoms of PMDD

While women with PMDD experience the typical physical symptoms associated with PMS, they also experience depression, anxiety, panic attacks, extreme irritability, rage, insomnia, a sense of overwhelm, poor stress management, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, and binge eating (3). Symptoms can be extreme to the point of suicidality. The distinguishing feature of PMDD as compared to other major depressive disorders is the temporal relationship between the onset of symptoms and the luteal phase of the cycle followed by resolution of symptoms with the onset of menses.

Risk factors associated with PMDD

Like other conditions, PMDD has associated risk factors that may predispose to its development. Epidemiological studies show an association with major depressive disorder, anxiety, PMS, family history of PMS/PMDD and a history of trauma. The association of trauma and PMDD may be linked to a heightened perception of stress and alteration in the stress response system. Other risk factors include cigarette smoking, obesity, and specific genetic variants (1).

Diagnosis of PMDD

PMDD may be superimposed on other mental health disorders which can make diagnosis difficult. The coexistence of PMDD with a diagnosed depressive disorder may interfere with accurate diagnosis as it is assumed that cyclical behavioral and mood changes are associated with a previously diagnosed disorder. Hormonal changes around pregnancy, childbirth, and perimenopause can worsen symptoms of PMDD due to the extreme level of hormonal fluctuations that occur during these events (1).

To differentiate between depressive disorders and PMDD, it is important to understand the timing of the onset of symptoms by asking the patient to keep a journal relating mood to the phase of the menstrual cycle over 2-3 months. To receive a diagnosis of PMDD, a patient must have at least 5 out of 11 specific symptoms that occur during the week before menstruation and improve within a few days after the onset of menses. The PMDD symptoms must occur for at least 2 menstrual cycles (1). These symptoms include:

- Mood swings

- Irritability or anger

- Anxiety, tension, feeling on edge

- Depression, feelings of hopelessness, self-deprecating thoughts

- Lack of interest in daily activities and relationships

- Fatigue, lethargy

- Feeling out of control

- Lack of concentration or trouble thinking

- Food cravings/binge eating

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Physical symptoms such as breast tenderness, aching muscles and joints, bloating, headaches

Menstrual magnification

Several psychiatric and physical disorders are exacerbated prior to menses such as IBS, migraines, depression, and anxiety. This is known as menstrual magnification or premenstrual exacerbation. The temporal relationship between the exacerbation of existing conditions may result in a provisional diagnosis of PMDD. However, just as it is important to make the distinction between PMDD and other disorders, it is also important to avoid misdiagnosing PMDD when other issues may exist that need appropriate assessment and treatment (4).

Causes of PMDD

Determining the cause of PMDD has proven to be complex with much contradiction throughout the literature. The interaction of neurotransmitters, genetic variations, enzyme activity, receptor activation, and thyroid and HPA axis function, set against the background of fluctuating ovarian hormones creates a multitude of variables that are difficult to capture in a single study.

Most studies suggest that reproductive hormone release patterns are no different in women with PMDD than in women without symptoms. It has therefore been presumed that women with PMDD may experience heightened sensitivity to cyclical variations in levels of reproductive hormones predisposing them to mood, behavioral, and somatic symptoms at an extreme level (1).

Neurosteroids (inclusive of pregnenolone, estradiol, and progesterone) are steroid hormones that are produced in endocrine tissue or the central nervous system that interact with neuronal receptors and have an impact on the level and activity of neurotransmitters such as GABA and serotonin. Estrogen and progesterone receptors are highly expressed in areas of the brain involved in emotion and cognition. Ovarian hormones can also act on multiple receptor types throughout the brain and exert immediate effects on synaptic activity. Ovarian hormones have neuroregulatory, neurotrophic, and neuroprotective effects in brain physiology so it is not surprising that fluctuations throughout the menstrual cycle would have effects on mood and cognition (5).

Progesterone and allopregnanolone

Allopregnanolone (ALLO) is a neurosteroid and a metabolite of progesterone. It can be synthesized in the central nervous system de novo from cholesterol, progesterone, or pregnenolone. ALLO exerts anxiolytic, anti-stress, and antidepressant effects by acting as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABA-A receptor potentiating the effects of GABA in the brain. ALLO is synthesized from progesterone through the sequential action of 5-alpha-reductase type I and 3-alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. These enzymes can account for the rate-limiting steps in the production of ALLO from progesterone (6).

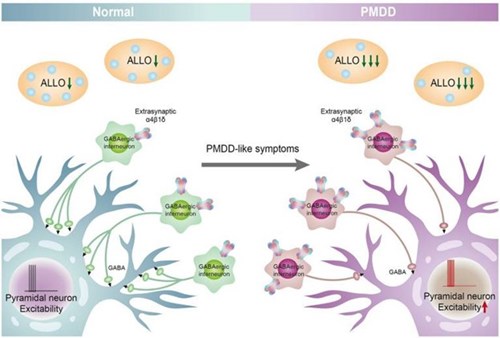

The sensitivity to hormonal fluctuations within the luteal phase of the cycle are mediated through the various subunits of the GABA-A receptor and ALLO. The majority of PMDD symptoms occur within the last week of the luteal phase when progesterone and its metabolite ALLO are declining. When the decrease in ALLO is rapid, there is an increase in the expression of certain GABA-A subunits that decrease their sensitivity to ALLO leading to an inhibition of GABA release. It is the reduction in GABA that contributes to the development of PMDD symptoms (2).

Instability and reduced plasticity within the GABA-A receptor subunits reduces the ability of the GABA-A receptor to adapt to fluctuating levels of ALLO. Under normal circumstances, ALLO will bind to the GABA-A receptor and enhance the GABA-gated chloride channel resulting in the release of GABA. When ALLO decreases too rapidly, the ability of ALLO to bind to the GABA-A receptor decreases resulting in a decrease of chloride influx and a decrease in GABA production. As stated by Gao et al, issues related to rapidly decreasing ALLO and its effect on GABA-A receptors is the main pathogenic factor in the development of PMDD and has become an area of exploration for treatment options focusing on the stabilization of the GABA-A receptor and its various subunits (2).

Figure 2. ALLO-mediated GABAA receptor subunit sensitivity participates in the pathogenesis of PMDD. When the decrease in ALLO is too rapid, there is an increase in the expression of GABAA receptor α4 β subunits (10) and decreases in the sensitivity (decreased affinity, reduced plasticity), and leading to a decrease in chloride influx, which, in turn, inhibits the release of GABA from GABAergic interneurons, reduces the inhibition of pyramidal neurons, and then increases the excitability of pyramidal neurons, leading to the development of PMDD. The ALLO-mediated GABAA receptor remains the main pathogenic factor of PMDD. (2)

SSRIs and ALLO

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered the gold standard for the treatment of PMDD. Studies have shown that SSRIs increase brain levels of ALLO without altering the brain levels of other neurosteroids. The concentration of ALLO in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) of 15 subjects before and after SSRI use over an 8-10-week period showed that the subjects with major depression had a 60% lower concentration of ALLO prior to SSRI use than non-depressed controls. In the depressed subjects, SSRIs normalized ALLO levels in the CSF. There was also a statistically significant improvement in depressive symptoms amongst the participants who received the SSRI (6).

When SSRIs are used to treat other depressive and anxiety disorders, the medication may take several weeks to have the desired effect. However, when used to treat PMDD, the effect is rapid and achieved at relatively low doses. As highlighted above, this is likely due to increased synthesis of ALLO. The rapid effect of SSRIs through this mechanism allows for dosing exclusively in the luteal phase of the cycle when PMDD symptoms occur (7).

Inhibition of progesterone and ALLO

Somewhat contradictory to the conclusions above, an article by Kaltsouni et al implicates progesterone and ALLO as the causative factors in PMDD. Their conclusion is supported by the fact that PMDD symptoms improve with anovulation resulting in low progesterone in the luteal phase with a return of symptoms when hormones are added back. In their study, they treated women with the selective progesterone receptor modulator (SPRM) ulipristal acetate and found a 41% reduction in PMDD symptoms. It was stated that the SPRM eventually leads to anovulation, but estradiol levels remained steady at mid-follicular levels. They conclude, as many studies do, that altered GABA-A receptor sensitivity to ALLO across the menstrual cycle is likely the cause of PMDD symptoms (8).

As reported by Carlini et al, dutasteride (Avodart) a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor commonly used in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia, inhibits one of the key steps in the production of ALLO. In a small double-blind placebo-controlled study, a 2.5 mg dose of dutasteride demonstrated significant efficacy in ameliorating anxiety, irritability, melancholy, bloating, and food cravings. Long-term use, however, is not recommended in women of child-bearing age but the study did seem to prove a point (7).

In a 2024 study by Ko et al evaluating the effect of estrogen, progesterone, cortisol, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), results revealed that women with PMDD who had higher levels of progesterone in the mid and late luteal phase experienced greater PMDD symptom severity. Additionally, women with PMDD who had a greater rise in progesterone from ovulation to mid luteal phase experienced more severe PMDD symptoms. Ko et al surmise that the cumulative sum of luteal phase progesterone correlates with increased severity of PMDD symptoms. They also cite studies in which the addition of progesterone can trigger PMDD is vulnerable women (9).

In these three studies, it is clear that PMDD symptoms are associated with the presence of progesterone and its metabolite, ALLO. Kaltsouni and Carlini prove that by completely inhibiting the production of progesterone and/or ALLO, either through inducing anovulation or by blocking the conversion of progesterone to ALLO, there can be a relief of symptoms. While this creates a clear link between PMDD and the presence of progesterone and ALLO, these studies do not reveal how these hormones contribute to PMDD. By eliminating progesterone, they have effectively eliminated the production of ALLO and the potential for any fluctuation of either hormone.

The Goldilocks principle and hormones – not too much, not too little, just right

The activity of any hormone can often be determined by the receptors available to receive it. We understand the principle of tachyphylaxis in which too much hormone will cause a down-regulation of its receptor, resulting in symptoms of deficiency for that hormone. Likewise, the positive effects of ALLO occur according to an inverse U-shaped curve showing that suboptimal levels (too low or too high) can be anxiogenic and optimal levels (just right) can be anxiolytic (5,2).

Most studies involve one or two serum measurements of the hormones of interest without actually seeing the dynamic fluctuation of these hormones from one day to the next within the luteal phase of the cycle. From a practical standpoint, study participants are not likely to submit to daily phlebotomy to measure hormones, but it is often the rapid decline in hormones that contributes to the onset of symptoms, and this cannot be captured with only one to two serum measurements within the luteal phase.

A broader perspective

Conditions other than PMDD that are associated with a rapid decline in hormones are post-partum depression, cyclical migraines, hot flashes, night sweats, brain fog, and emotional lability. Hormones rise and fall within the luteal phase of the cycle so everything that is under the influence of these hormones experiences that rise and fall and must adapt to these changes. The typical progesterone curve in the luteal phase actually looks like a roller coaster ride where you might experience one set of symptoms going up and an entirely different set of symptoms going down. At the bottom of the downslope is when everything levels out and there is a chance to equilibrate.

A woman’s unique history, physiology, genetics, diet, lifestyle, and foundational health can influence her experience of fluctuating hormones. Rather than completely eliminating the menstrual cycle, the goal should be to create a background of stability that can buffer the effects of cyclical changes. We may not be able to completely eliminate mood and physical symptoms associated with fluctuating hormones, but with knowledge of the potential contributors, we can provide much needed support.

In part II of The Complex Web of PMDD, we will explore the effects of estrogen, thyroid, and stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis on the symptoms of PMDD. Testing for underlying causes related to thyroid and adrenal function, as well as assessing hormonal fluctuations within the cycle, can provide actionable data that may create more stability within the endocrine system as a whole. We will also review some common conventional treatments and integrative and alternative approaches to addressing this disorder.

References

- Mishra S, Elliott H, Marwaha R. Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. [Updated 2023 Feb 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

- Gao, Qian, et al. “Role of Allopregnanolone-Mediated γ-Aminobutyric Acid A Receptor Sensitivity in the Pathogenesis of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Toward Precise Targets for Translational Medicine and Drug Development.” Frontiers in Psychiatry, vol. 14, 2023, p. 1140796.

- Cleveland Clinic - “Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD).”

- Massachusetts General Hospital - The Etiology of PMDD

- Barth, Claudia, et al. “Sex Hormones Affect Neurotransmitters and Shape the Adult Female Brain during Hormonal Transition Periods.” Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 9, Feb. 2015, p. 37.

- Paul, Steven M., et al. “Allopregnanolone: From Molecular Pathophysiology to Therapeutics. A Historical Perspective.” Neurobiology of Stress, vol. 12, Mar. 2020, p. 100215.

- Carlini, Sara V., et al. “Management of Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: A Scoping Review.” International Journal of Women’s Health, vol. 14, Dec. 2022, pp. 1783–801.

- Kaltsouni, Elisavet, et al. “Brain Reactivity during Aggressive Response in Women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder Treated with a Selective Progesterone Receptor Modulator.” Neuropsychopharmacology, vol. 46, no. 8, July 2021, pp. 1460–67.

- Ko, Chih-Hung, et al. “Estrogen, Progesterone, Cortisol, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor during the Luteal Phase of the Menstrual Cycle in Women with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder.” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 169, Jan. 2024, pp. 307–17.

- Lovick, T. SSRIs and the female brain--potential for utilizing steroid-stimulating properties to treat menstrual cycle-linked dysphorias. J Psychopharmacol. (2013) 27:1180–5. doi: 10.1177/0269881113490327