The American Heart Association has designated the month of February as American Heart Month to raise awareness about heart disease and the healthy choices we can make to prevent it. Every year, 1 in 4 deaths are caused by heart disease. And while some risk factors are out of our control, such as family history, genetics, and aging, most of the risk factors for developing heart or cardiovascular disease are more often than not within our control. For example, lifestyle habits and behaviors such as smoking cessation, physical activity, healthy food selection, and how we cope with mental and emotional stressors, like feeling angry, can be modified [1].

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in women and the risk dramatically increases with menopause. Although there are many factors involved in the development of CVD, there is speculation that the hormonal shifts experienced during the transition into menopause may play a part. Estrogen is one of the key transitional hormones during this changeover and its low levels during menopause are strongly associated with increasing cardiovascular risk. For its role in several aspects of cardiovascular disease prevention, estradiol has been the subject of various investigations through the years.

What we know now is that estrogen replacement therapy actually decreases cardiovascular risk when prescribed early in menopause. |

Estrogen Research Through the Years

Estrogen’s cardioprotective properties haven’t always been well understood. Early analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) incorrectly attributed the negative cardiovascular side effects of co-administered medroxyprogesterone acetate to Premarin. This sent the field of hormone replacement therapy into a serious identity crisis. What we know now, after years of further analysis and from a great many follow-up studies to the WHI, is that estrogen replacement therapy actually decreases cardiovascular risk when prescribed early in menopause. This occurs by several different mechanisms, the physiology of which I will describe after a brief review of the research comparing the cardiovascular risks associated with oral vs. transdermal estrogens [2][3][4].

With further analysis of data from the Women’s Health Initiative-Estrogen Study (WHI-E) and comparisons with the earlier findings, researchers proposed the “timing hypothesis” which suggested there was a difference in outcomes when hormones were replaced at specific stages of the menopausal transition. For example, the data showed menopausal hormone replacement was cardio-protective if it was initiated in women who were perimenopausal or early postmenopausal, whereas starting estrogen replacement in late postmenopausal women (>10 years) showed either no benefit or detrimental effects on the cardiovascular system [5].

Another follow-up study of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial compared different types, doses, and delivery routes of hormone therapies in relation to cardiovascular disease outcomes. Specific types included oral conjugated equine estrogens (CEE), i.e., Premarin, with and without a progestin; oral estradiol (E2), with and without a progestin; or progesterone plus transdermal estradiol. Women within less than 5 years from the onset of menopause when CEE therapy was initiated had a lower absolute cardiovascular risk than women placed on CEE therapy more than 10 years from onset. While comparisons between oral CEE and transdermal estradiol were not significantly different for CVD outcomes, data suggested transdermal delivery lowered the risk of major coronary heart disease (CHD) compared to oral delivery [6].

A widespread type of coronary heart disease is also called coronary artery disease (CAD) or atherosclerosis [7]. Atherosclerosis is a disease of vascular aging in which changes to the endothelium, the inner lining of the blood vessels, contribute to formation of plaques, which are a combination of blood proteins, lipids and calcium that congregate and adhere to the walls of damaged arteries. Plaque build-up narrows or blocks arteries and decreases blood flow. In addition, the hardened plaques reduce the intrinsic, elastic nature of the arterial endothelium.

Endothelial Dysfunction’s Role in Cardiovascular Disease

Vascular aging has elements of endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis development and is a major risk factor for developing CVD. The menopause transition seems to accelerate vascular aging, and estrogen decline contributes to this in several ways.

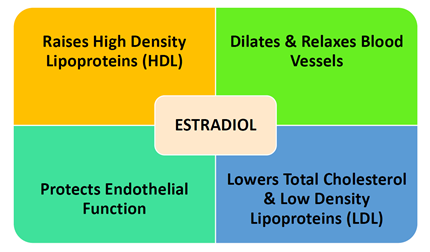

Known actions of estrogen include the following: raising high density lipoproteins (HDL), lowering cholesterol and low-density lipoproteins (LDL); dilating and relaxing blood vessels; and protecting endothelial function. Changes in blood lipid levels, vascular tone and the endothelial cells are major risk factors for developing cardiovascular disease.

The term “endothelial dysfunction” is used to describe defects in the production or bioavailability of endothelial-derived nitric oxide (NO) and the consequential damaging changes in vascular dilation or reactivity. Nitric oxide is produced throughout the body to promote various functions in different tissues. In the cardiovascular system, its primary role is to control vascular tone, dilate blood vessels, reduce blood pressure and inhibit platelet aggregation in arteries to prevent clotting and thrombotic events. Estrogen has been shown to enhance NO production through estrogen receptor (ER)α-mediated activation of nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in endothelial cells. Extended times of lower estrogen can reduce ERα expression causing functional impairment of ERα/eNOS signaling [8].

Endothelial function is seen to gradually decline in men over 40, but the decline in women begins at 50 years of age and accelerates after menopause as estrogen levels plummet. Via ultrasound, brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) was used to measure endothelial-dependent vasodilation in healthy premenopausal, perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Results for vasodilation were highest in premenopausal women, lower in perimenopausal women and lowest in postmenopausal women. Higher FSH and lower estradiol concentrations also correlated with lower brachial artery FMD measurements as women transitioned through menopause. Conclusions were made indicating endothelial dysfunction worsened in late menopause when ovarian function and estrogen deficiency were at their lowest [9].

Estrogen replacement in menopause can stimulate NO release to help regulate inflammatory cytokines. |

Estrogen also displays antioxidant effects and protects against oxidative stress, which is another key mechanism of endothelial dysfunction. It may play an inhibitory role in the scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can suppress or scavenge nitric oxide. Furthermore, with aging and estrogen deficiency, the inflammatory marker tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), is up regulated. This in turn activates the expression of adhesion molecules and cells to attach to the walls of the blood vessels creating more inflammation and plaque formation. TNFα will also scavenge NO, decreasing its bioavailability and setting up a cascade of events increasing inflammation. Estrogen replacement in menopause can stimulate NO release to help regulate inflammatory cytokines [8][10].

Estrogen Replacement: Timing Is Key

The critical window for stemming cardiovascular or coronary heart disease has been shown to be the time when estrogen appears to begin its descent [11]. Trying to “re-estrogenize’ women who are already in late menopause with estrogen replacement may not result in the expected changes seen in early perimenopausal women. Perhaps this is because longstanding estrogen deficiency alters the epigenetic terrain to the extent that the body will no longer react as favorably to estrogen supplementation.

To that end, the importance of initiating estrogen therapy early in menopause for cardiovascular health cannot be overstated. Without estrogen’s role in modulating the vascular effects of nitric oxide and TNFα, and its influence on blood lipids, women are left at greater risk of a cardiovascular event and more likely to end up on a polypharmacy collection of statins, hypertension, and anti-inflammatory drugs which all carry their own risk of adverse outcomes. It’s time to consider the female physiology with the evidence on estrogen replacement if we want to stem the tide of cardiovascular disease.

To find out if you are estrogen deficient, ZRT offers estradiol testing in four body fluids for your convenience – saliva, blood spot, dried urine, and serum. Learn more about hormonal imbalances during menopause and order your next test kit today.

Related Resources

- Blog: Mood and Menopause - Going Through "The Change"

- Webinar: Estrogen Metabolism & Breast Cancer Risk

- Web: Menopause

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Fact Sheet: Heart Disease.

2. Grodstein F, et al. A prospective, observational study of postmenopausal hormone therapy and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:933-41.

3. Grady D, et al. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS): design, methods, and baseline characteristics. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:314-35.

4. Rossouw JE, et al.; Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321-33.

5. Phillips LS, Langer RD. Postmenopausal hormone therapy: critical reappraisal and a unified hypothesis. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:558-66.

6. Shufelt CL, et al. Hormone therapy dose, formulation, route of delivery, and risk of cardiovascular events in women: findings from the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Menopause. 2014;21:260-6.

7. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Fact Sheet: Know the Differences. Cardiovascular Disease, Heart Disease, Coronary heart Disease.

8. Moreau KL, Hildreth KL. Vascular Aging across the Menopause Transition in Healthy Women. Adv Vasc Med. 2014;2014:204390.

9. Moreau KL, et al. Endothelial function is impaired across the stages of the menopause transition in healthy women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4692-700.

10. Clarkson TB. Estrogen effects on arteries vary with stage of reproductive life and extent of subclinical atherosclerosis progression. Menopause. 2018;25:1262-1274.

11. Giordano S, et al. Estrogen and Cardiovascular Disease: Is Timing Everything? Am J Med Sci. 2015;350:27-35.