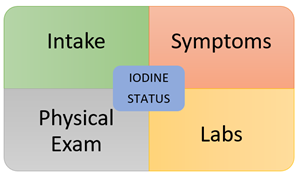

I’m excited to do this practical piece on iodine therapy because I field a lot of questions on the matter of assessing iodine status, implementing the right iodine supplement, and monitoring that therapy.

Iodine performs some crucial roles in the body, but it never acts alone. Therefore, to assess iodine deficiency, it’s imperative to test iodine and its partners - selenium, iron, magnesium, zinc, B6, cortisol, and glutathione. To assure optimal outcomes, it’s also important to check for endocrine disruptors like bromine, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic.

Iodine's Relationship to Health

If you do an online search for information on “iodine supplementation,” you’re bound to find most of the articles focused on the thyroid and on the iodide form of the mineral. But many providers are now thinking about iodine’s relationship to the breast, to ovarian health, to ovulation and fertility, and even in the context of cancer prevention and treatment.

Even beyond nutritional sufficiency, many are using iodine in supraphysiologic doses to get more of a drug-like effect. I think much of the information out there on iodine, while exciting and informative, can be confusing when it comes to discerning a clear treatment for a patient’s unique presentation.

Given that, this guide will focus on the “how to” of assessing for and treating iodine deficiency rather than the “why you should,” and I’ll connect you with the various ZRT resources already available to help you implement this assessment in practice.

Iodine Intake

The first part of any good nutritional evaluation – assess for adequate intake. As clinicians, we may gloss over this part or take patients at their word. It’s great when patients give their assurance that they have a “clean diet” or “only eat a diet rich in whole, organic foods” but that doesn’t necessarily tell you what exactly they’re eating on a regular basis. This is where a diet recall during the visit followed up by a 7-day diet diary can be helpful. And what key foods should you be looking for? Check out these two resources below.

Even if someone eats an excellent diet that should yield an adequate daily iodine intake, unfortunately natural food sources may vary somewhat in nutritional content which affects dietary intake. We should also consider assessing for consumption of toxic elements that disrupt iodine uptake like bromine and arsenic [1][2].

Key Symptoms

While it’s tempting to rely on nutritional intake for information about a patient’s overall iodine status, it’s important to consider an individual’s symptom profile. Is she presenting with fibrocystic breasts? Is he suffering with benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH)? Some examples of presentations that may warrant an investigation into low iodine status are:

- Athletes (sweating clears more iodine, increases requirement)

- Breast cancer - Family or personal history

- Fibrocystic breast changes (and breast pain)

- Gastric cancer

- Hypometabolism/hypothyroidism - Weight gain, low body temps, constipation, fatigue, dry skin, brittle nails

- Hypochlorhydria or Gastric Bypass (may decrease absorption)

- Infertility - Ovulation – Women; Semen quality - Men

- Lactation

- Menstrual cycle irregularities - Mid-cycle pain

- Ovarian cysts (luteal cysts)

- Pregnancy

- Urinary symptoms in men due to prostate problems (including prostate cancer)

Physical Examination

I don’t know of a clear “tell” when it comes to identifying an early iodine deficiency, but perhaps the first sign would be decreased sweating as the body tries to decrease iodine clearance. Once that low status reaches the thyroid, clear signs begin to emerge.

Hypothyroidism symptoms

- Brittle fingernails

- Hair loss, diffuse

- Puffy eyes

- Subnormal body temp

- Decreased sweating

- Hoarse speech

- Skin dry/coarse

- Thyroid enlargement

- Edema (non-pitting)

- Lateral 1/3 eyebrow loss

- Slow heartrate

- Hair dry/coarse

- Overweight

- Slow reflex return

Other signs that may suggest a low extrathyroidal iodine status (or a need for supplemental iodine):

- Breast exam may reveal bilateral diffuse bumpiness or focal areas that are often tender to palpation.

- Prostate exam may reveal diffuse, bilateral bogginess.

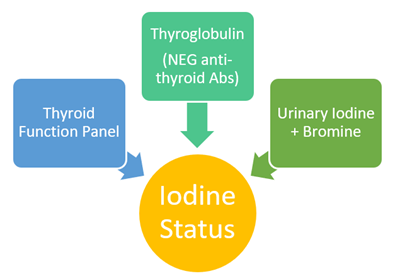

Laboratory Assessment: 3 Parts

Essential Components: TSH, Total T4, Free T4, Free T3

How does a thyroid function panel tell us about iodine status? Well, to answer that, here’s a super basic look at the pertinent physiology as we follow the iodine after dietary consumption over to the thyroid and then to the rest of the body. After being absorbed into the thyroid tissue, iodine accumulates and incorporates into the structure of the main thyroid hormone, thyroxine (T4). With iodine deficiency, T4 levels fall (total T4 drops earlier than free T4) and TSH levels rise to increase iodine absorption capability [3].

T4, as the body’s main source of metabolic potential energy, in true endocrine fashion travels through the body attached to thyroid binding globulins (total T4) to target tissues where it becomes free T4. When T4 is “activated” in the tissues to T3, iodine is liberated into the intracellular space.

In this way, the thyroid is in large part responsible for the dissemination of iodide to the body through conversion of T4 to T3 far from the thyroid itself. Several nutritional cofactors such as zinc, selenium, and vitamin B6 make the conversion of T4 to T3 possible, and deficiencies in these diet-acquired cofactors can lead to low T3 levels, low intracellular iodine levels, and symptoms. So, for this reason, when assessing intracellular, extrathyroidal iodine status, it is absolutely insufficient to test only T4 and TSH. We must look to free T3 for that additional piece.

Notes for testing: When initiating supplemental iodine (and the same goes for thyroid hormone replacement), monitoring a thyroid function panel at 6-8 weeks is recommended for reassessment.

2. Thyroglobulin (+ Antibodies to TPO and TG)

When thyroglobulin (Tgbn) is higher in the context of an otherwise normally functioning thyroid, it’s likely the thyroid is laboring to overcome an iodine deficiency. The scarcer iodide is to the thyroid, the more the thyroid gland enlarges due to increased stimulation from TSH. The denser the thyroid tissue, the more thyroglobulin. Likewise, when thyroglobulin is optimal (3 – 10 ng/mL), iodine has been sufficiently available for adequate thyroid hormone production and any variations in dietary iodine intake has likely been well-sustained by the thyroid [4][5].

Caveat: When using thyroglobulin to assess iodine status, it is important to either have previously confirmed or simultaneously test for anti-TPO and especially anti-Tgbn antibodies because autoimmune thyroid tissue destruction can also cause increases in thyroglobulin unrelated to iodine status. Importantly, if you’re considering molecular iodine-only supplementation, this information influences the level of monitoring necessary during that treatment.

3. Urinary Iodine and Bromine

Urinary iodine measured via ICP-MS is a direct and simple way to test for recent iodine sufficiency without the interference from bromine found with ion electrode testing. Traditional ion electrode testing can’t tell the difference between iodine and bromine. But even ICP-MS iodine testing is inappropriate for discerning longer-term iodine status without putting it together with the aforementioned thyroid markers.

Other methods of testing for functional iodine deficiency have frustratingly fallen short of the scientific bar. In particular, the “iodine loading test” can no longer be recommended due to its premise being based on a long-propagated misapplication of earlier literature exploring the expected iodine clearance after a high dose of iodine and very low sensitivity as a result. Dr. Zava has written about the flaws associated with the iodine loading test in a white paper you can find here and ZRT actually did a small study to assess the iodine clearance and kinetics after a 50 mg dose of iodine/iodide mixture you can read about here.

Notes for testing: For a baseline urinary iodine level for those previously supplementing, the recommendation varies by the previous dose. After stopping supraphysiologic dosing (1100 µg – 6.0 mg), 7-10 days is usually enough time to return to baseline. For those using physiologic doses (150 µg – 1100 µg), 3 days off is recommended. After a CT scan with iodine contrast or dosages > 6.0 mg, it can take 4 – 6 weeks to clear that iodine. Lab values can reach the tens of thousands for those who test too early afterward!

Urinary Bromine via ICP-MS tells us about iodine status because bromine impedes iodine’s entry into the thyroid gland. That means even when urinary iodine levels are normal, if bromine is elevated, tissue iodine levels may actually be inadequate. As such, this element should always be assessed side by side with iodine.

Overview: Laboratory Clues of Low Iodine Status

| Analyte | Finding | ZRT Range |

| TSH | ↑ | 0.5 – 3.0 µU/mL |

| Total T4 | ↓ | 5 – 10.8 µg/dL |

| Free T4 | ↓ | 0.7 – 2.5 ng/dL |

| Free T3 | ↓ (or low compared to fT4) | 2.4 – 4.2 pg/mL |

| Thyroglobulin | ↑ (when negative anti-thyroid antibodies) |

3-40 ng/mL ZRT Optimal 3-10 ng/mL |

| Urinary Iodine | ↓ | 100 – 380 µg/g Cr |

| Urinary Bromine | ↑ | <4800 µg/g Cr |

Note: Free T4 and Free T3 may be within normal ranges for a period of time as the body works to accommodate for an iodine deficiency

Final Thought on Iodine

In a world full of endocrine disruptors, misguided diets, and daily stressors, it is very easy for people to fall below their individual nutritional intake requirements. Given iodine’s responsibilities inside and outside the thyroid, its sufficiency is so important for all of our patients. When symptoms of iodine deficiency start to emerge, follow these guidelines to investigate the signs. Once a clinical pattern materializes to correlate with those symptoms, the next step involves choosing an iodine supplement regimen.

Related Resources

- Handout: Iodine Content in Foods

- Blog: Guide: How to Treat Iodine Deficiency

- Blog: How 5 Elements Can Affect Your Thyroid Hormones

References

1 Lee KW, et al. Food Group Intakes as Determinants of Iodine Status among US Adult Population. Nutrients. 2016.

2 Shengwen S, et al. Arsenic binding to proteins. Chem Rev. 2013; 113(10): 7769–7792.

3 Pearce, EN, et al. Urinary iodine, thyroid function, and thyroglobulin as biomarkers of iodine status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016; 104(Suppl 3): 898S–901S.

4 Andersen S, et al. Reliability of thyroglobulin in serum compared with urinary iodine when assessing individual and population iodine nutrition status. Br J Nutr. 2017;117(3):441-449.

5 Ma ZF. Thyroglobulin as a biomarker of iodine deficiency: a review. Thyroid. 2014;24(8):1195-209.